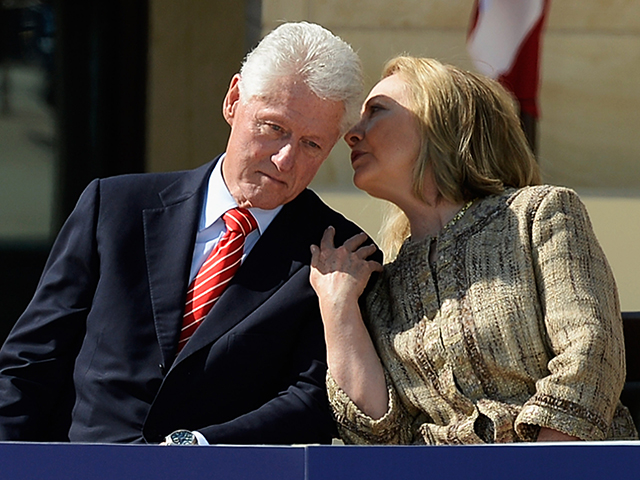

The Clinton White House was the first administration in history to contend with the rise of the Internet, and its dramatic transformation of the modern media landscape. The advent of the digital era smashed the Left’s media monopoly, and, according to papers released last week, the Clintons were prescient about the impact this new technology would have.

While occupying the governor’s mansion in Little Rock and later at the White House, the Clintons were famously conspiracy-minded—a paranoia that earned them the sobriquet The Arkansas Borgias. But they had a right to be wary about the power of the Internet. And, as made clear by the cache of papers released by the Clinton Library last Friday evening, the Clinton’s didn’t like its potential one bit.

In the awkwardly named Communication Stream of Conspiracy Commerce memo—which is heavily redacted from 331 pages to a mere 28 and whose author remains unknown—the Clinton’s paranoia is on display. Much of the memo is devoted to detailing how news they didn’t like was suddenly being given credence. One paragraph in particular is almost prophetic:

The internet has become one of the major and most dynamic modes of communication. The internet can link people, groups and organizations together instantly. Moreover, it allows an extraordinary amount of unregulated data and information to be located in one area and available to all. The right wing has seized upon the internet as a means of communicating its ideas to people. Moreover, evidence exists that Republican staffers surf the internet, interacting with extremists in order to exchange ideas and information.

One almost feels pity for the Clintons, as they huddled Macbeth-like in their castle (our White House) assessing the media furies gathering outside. It was true that the Internet did allow an extraordinary amount of unregulated data to—for the first time in history—become available to all. It must have dawned on the Clintons that this was the end of an era; the days when three networks and a couple of newspapers defined the “news” were all but over.

The memo outlines in detail how they saw the new universe working:

This is how the stream works. First, well funded right wing think tanks and individuals underwrite conservative newsletters and newspapers such as the Western Journalism Center, the American Spectator and the Pittsburgh Tribune Review. Next, the stories are reprinted on the internet where they are bounced all over the world. From the internet, the stories are bounced into the mainstream media through one of two ways: 1) The story will be picked up by the British tabloids and covered as a major story, from which the American right-of-center mainstream media (i.e. the Wall Street Journal, Washington Times and New York Post) will then pick the story up; or 2) The story will be bounced directly from the internet to the right-of center mainstream American media. After the mainstream right-of-center American media covers the story, Congressional committees will look into the story. After Congress looks into the story, the story now has the legitimacy to be covered by the remainder of the American mainstream press as a “real story.”

In those (now we know) waning days of dead-tree dominance, what really irked the Clintons was the jump from British tabloids to mainstream media to congressional oversight to the remainder of the traditional media. My colleague Nile Gardiner, director of the Margaret Thatcher Center for Freedom, points out that:

The British press has a long tradition of fearless investigative reporting, with little deference towards politicians in general. UK newspapers have for decades published hard-hitting pieces critical of sitting U.S. presidents, stories that would not be run by the U.S. mainstream media for fear of offending the White House.

The Clintons tried to arrest this metamorphosis by meeting with reporters and editors, and sharing the memo with friendlies at the major newspapers back in 1995.

The memo’s existence first came to light in 1998 when newspapers reported on it and some reporters acknowledged having received it, but it first saw the light of day (albeit in its redacted form) last week.

The Heritage Foundation makes the cut, being mentioned a few times as one of the conservative think tanks that were part of the “stream” as was one of our top donors and founders, Richard Mellon Scaife.

And, for whatever it’s worth, the Internet has indeed become the liberating force that the Clintons foretold back then. What role it will play with regard to the Clintons’ future (if any) political aspirations remains to be seen.