A modern retelling of “The Little Red Hen” would include ducks and pigs that not only didn’t help grow the wheat and bake the bread, but who wanted to eat the bread after hobbling the Red Hen while she did the work.

Politicians in both Washington and New York want to reduce income inequality while blocking access to valuable energy resources. The poor might be better helped if those politicians looked at North Dakota’s experience over the past decade.

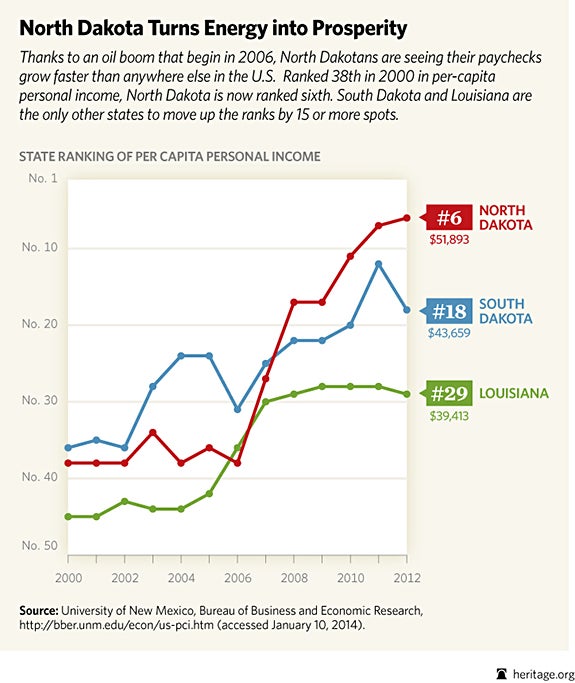

In 2006, North Dakota ranked 38th among the states in average personal income. By 2012, it was sixth. Department of Commerce data show that over those six years, North Dakota’s per capita personal income went from 14 percent below the national average to 25 percent above.

Some might argue that the only lesson here is that it’s great to have petroleum reserves. But they are missing a bigger picture: Making a bigger pie helps more than keeping a pie small and slicing it into more pieces.

And to make the pie bigger, people need to be allowed to take advantage of opportunities when they arise.

For instance, the Marcellus shale, which has been the biggest new source for the nation’s natural gas renaissance, is for the most part located beneath New York and Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania has allowed landowners to rapidly develop the reserves they own, while New York has maintained a moratorium on the smart-drilling technology (hydraulic fracturing and directional drilling) that unleashes the gas.

The farmers on the New York side of the state line gnash their teeth, while the farmers in Pennsylvania cash their checks. One state grabbed the brass ring while the other thumbed its nose at jobs, income and lower energy prices.

Nationwide, we see something similar. Our stunning increase in petroleum production (nearly 40 percent in the past three years) has occurred almost exclusively on state and private land. In fact, production on federal land dropped over the past couple of years.

One statistic epitomizes why that is so: In North Dakota, it takes about 10 days to get a drilling permit. In contrast, the delay for a federal drilling permit is about 10 months—double what it was in 2005.

You’d think that an administration that is so intent on redistributing income would be a little more sympathetic to generating the income in the first place.

Of course, the income growth in North Dakota was not evenly spread. Income growth never is. But programs to help the poor are a lot easier to afford when government runs a surplus generated by a booming economy (as in North Dakota) than when government runs record deficits (like our federal government).

It’s also true that growth comes with costs. When my son grew from 5 feet 4 inches to 6 feet 4 inches, we had to continually buy new clothes. But clothing cost is hardly an argument for stunting a child’s growth.

While less trivial than the cost of new clothes, the costs of housing, road repair and public services are small compared to the benefits of overall economic growth, as the condition of state finances in North Dakota attests.

Few states are blessed with a Bakken shale formation. So, where significant energy resources (or other assets for that matter) exist, it seems a no-brainer to take advantage of them. Sadly, that is not universally the case.

Ironically, some who most fervently thwart access to the resources are equally fervent about doing something to help the poor. Here’s a suggestion for a first step in helping the poor: At least give them a chance to bake the bread.

Kreutzer is a research fellow in energy economics and climate change at The Heritage Foundation. This piece originally appeared in the Grand Forks Herald.