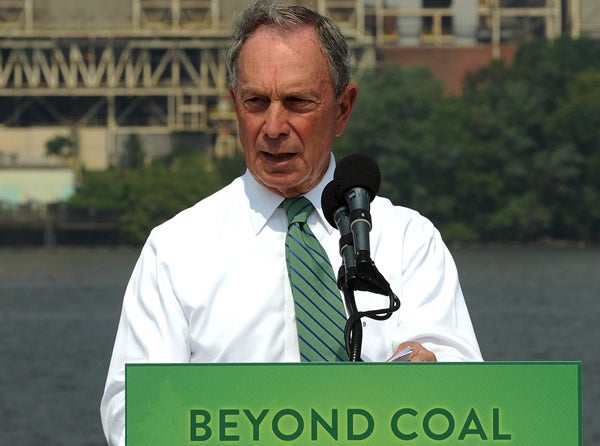

In a Sunday New York Times article about public pension costs, Mayor Michael Bloomberg has the following quote: “If I can give you one piece of financial advice: If somebody offers you a guaranteed 7 percent on your money for the rest of your life, you take it and just make sure the guy’s name is not Madoff.”

Bloomberg was referring to a common problem with public pension accounting: In order to claim that they have enough money to pay future retirement benefits, fund managers assume that their investments will return 7–8 percent per year. There is nothing wrong with having a target or expected rate of return, but pension benefits are guaranteed. These benefits must be paid regardless of whether the funds hit their targets.

When future benefits are guaranteed, a basic principle of financial economics teaches that actuaries must discount (reduce the value of) those future benefits at a risk-free rate, which is currently around 2–3 percent, not 7–8 percent.

Bloomberg’s point is that it is “indefensible” (his word) to assume that pension funds can achieve high rates of return without anyone worrying about risk. Of course, using a lower discount rate means that public pension costs are much greater than what government actuaries claim, since lower investment earnings means more taxpayer contributions needed to pay benefits.

The Heritage Foundation released two new papers today that detail the real cost of public pensions. This Backgrounder is a comprehensive and technical discussion of how to estimate pension costs using the risk adjustment advocated by financial economists. This Issue Brief, aimed at a wider audience, is the short version of the Backgrounder.

The Issue Brief uses the Wisconsin Retirement System (WRS) as an example. As also detailed today in an op-ed for the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, proper risk-adjusting indicates that the WRS costs more than 2.5 times what the state claims. Seen in that light, the public-sector reforms signed by Governor Scott Walker (R) are rather modest.

Wisconsin is far from unique in underestimating its pension costs, and nationwide reform is unlikely until taxpayers have a clear sense of what the real costs are.